The “rough sex” defence was outlawed on Monday 6 July 2020 in England and Wales. The amendment forms part of the new Domestic Abuse Bill, which is entering the Report Stage in the House of Commons. This is an important step for the justice system and for people, particularly women, who experience abuse, and we need to use it to shine a spotlight on the perturbing and all-too-familiar tendency to victim blame when a serious crime has been committed.

Victim blaming is where a perpetrator’s crime, and let’s not forget that committing domestic abuse is a crime, is held partially or entirely at the fault of the victim. For example, they “asked for it”, “they liked it”, were “too weak”, “didn’t ask for help”.

The “rough sex” defence is used in court to justify a person’s death or injury by claiming sex “went wrong”. The new clause passed this week rules out “consent for sexual gratification” as a defence for causing serious harm.

As Labour’s Harriet Harman, who led calls for the law to change, says “The whole system is failing victims. Rape is such a serious crime, a violation of a woman both physically and mentally, it is important defendants are brought to justice.”

Over the last decade, 60 women in the UK had been killed by men who claimed in court the women were “consenting” to the violence, research by the campaign group We Can’t Consent To This shows. That’s a staggering statistic. That any woman could “consent” to being murdered is baffling, and it’s devastating that any police investigation or court would drop or rule out a case on this basis.

According to Home Office statistics in England and Wales, only 1.7% of reported rapes are prosecuted. It is feared that there are thousands of cases of sexual abuse of women that never get reported, for the very fear that they will be blamed for what happened to them.

Many victims are aware that the “rough sex” defence could be used, and so never disclose the crime that was committed against them, sadly to even friends and family let alone the police, which means that the actual number of sexual assaults is far far higher.

We really do hope this new clause will mean that more women will feel more confident in speaking out. But often victims, and let’s remember that they are victims, feel too vulnerable to go through with a report of rape or abuse.

Real change will need to be seen and experienced in attitudes towards victims before the real work happens to address this injustice. We’ll need to start seeing that the outcome when perpetrators make this defence in court changes before we can declare progress has been made – when the focus shifts to the intention of the act and the damaging exertion of power over a victim, that abuse is recognised and subsequently defendants are charged.

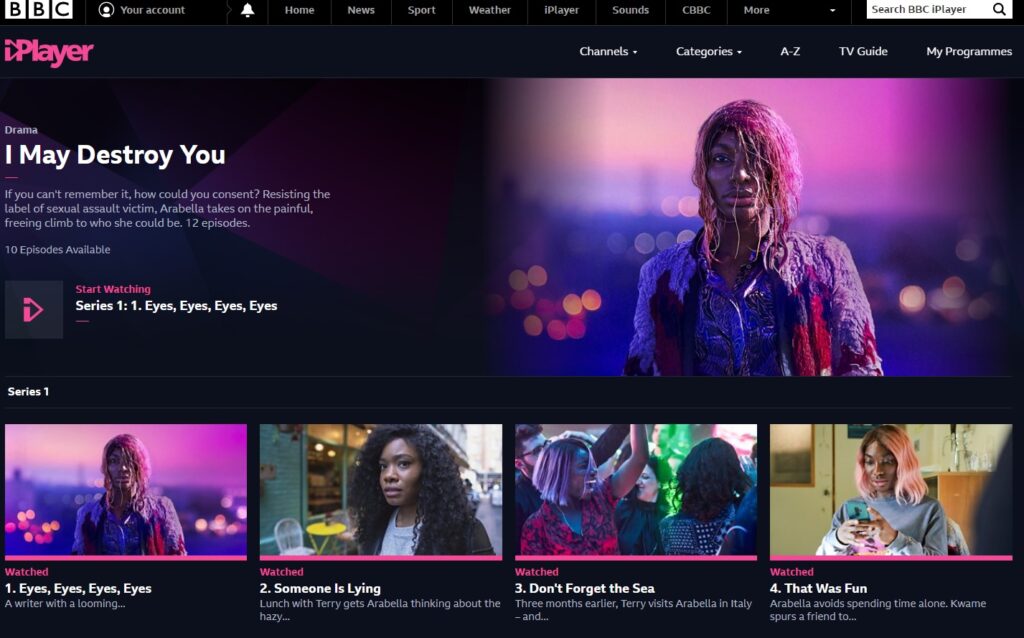

The hugely compelling and important new BBC drama I May Destroy You, written by and starring the talented Michaela Cole, addresses the issues of consent and sexual abuse in one of the most compelling portrayals we’ve ever seen on screen. It’s a welcome and much-needed wake-up call to the experiences women, and men, deal with and the blurred lines that should be crystal clear to us all.

Arabella, an up-and-coming writer, struggles to remember the events that took place during her night out with friends, but she soon realises that she was drugged and taken advantage of. The story follows Arabella and her circle as she tries to piece together what happened, her journey of reporting the assault to the police and it’s subsequent ‘dead end’ and the pervasive and problematic acts of abuse of trust, consent and power.

Victim blaming is used to ignore and suppress the act of abuse, particularly in relation to women. We often hear “why don’t they just leave?” when talking about victims of domestic abuse. The focus here is wrong, why are we focusing on the victim’s ‘responsibility’ and not the perpetrator’s acts? The questions we need and should be asking are:

- Why do they insist on harming the people they are supposed to love?

- Why don’t they change his behaviour?

- Why does it always become the victim’s fault, why is their responsibility?

- What can we do as an individual/organisation/society to call out abuse, support victims, hold perpetrators accountable and help them to address their issues?

Leaving an abusive relationship is a very long and difficult process.

Leaving is a process and not an event. It’s important to remember that violence/abuse and risk increase at the point of leaving a relationship. This is made difficult for a range of reasons. If someone is experiencing domestic abuse they may:

- Feel ashamed and reluctant to tell people or seek help

- Feel frightened and uncertain about what the future will hold

- Feel it’s in the children’s best interests to stay

- Abuse can reduce the ability to make big decisions being isolated from family and friends means making big decisions alone, without a support structure

- Financial abuse and shared finances can make leaving difficult

- Knowledge about the services available can be limited

- They might have received a negative response when they reached out to someone for support in the past

- Still have feelings for their partner and hope that the relationship will get better

Victims are constantly in survival mode, and sometimes this becomes a freeze situation, unable to make steps to safety or reach out for help.

Perhaps they have known nothing else, or feel shame, shock, or overwhelm… they can wrongly blame themselves. Coupled with the media’s tradition of victim blaming women with its click-bait culture – just look at the case of the murder of backpacker Grace Millane – and society’s obsessive culture of focusing on what the woman is or isn’t doing, has or hasn’t done, and it becomes a melting pot for misperceptions and misappropriated fault.

The Government’s new Domestic Abuse Bill is a start to creating change, but it takes all of us to take responsibility for how we perceive cases of abuse and the victim’s role – we must at all times remember that they have had a crime committed against them, they have experienced something that is hugely traumatic, and that recovering from that trauma can take a long time, sometimes a lifetime. The experience will never not be there.

We work with young people and schools to educate and inform them about consent and healthy relationships because we believe that the earlier they are aware and understand, the safer their world and life experiences, we hope, will be. We educate parents, teachers and pastoral staff too. Our Just So You Know workshop is delivered in schools, focussing on consent, grooming and healthy relationships. In the last year, 664 children and young people attended these workshops across Kent.

We help companies and organisations put policies in place to support victims of abuse and offer community groups resources to inform and educate. We have important information on what domestic abuse is, how to look for signs, how to help yourself or someone you know to plan their journey to safety. And of course, our refuges and safe accommodation are helping survivors and their families rebuild their lives.

*All images used on this website are representative. All names are anonymised for people’s safety.